Across Australia’s vast outback, parasitic worms are crippling sheep production. The little-known, blood-sucking Barber's Pole worm is one of the most dangerous, commonly killing infected sheep.

Worse still, drugs traditionally used to eradicate worms are no longer effective, resulting in rising “drench resistance”, or larger populations of worms surviving and passing on resistant genes.

The blow to the sheep industry has grown to $400 million a year, more than any other disease, at a time when agricultural exports are becoming more important to the economy amid less mining investment.

Samantha Nixon, a PhD student from Professor Glenn King's lab at The University of Queensland's Institute for Molecular Bioscience and CSIRO, says a recent survey found that 90 per cent of Australian sheep properties have drug resistance in the worms, critically impacting production. However, her team may have the answer: spider venom.

“We desperately need new treatments,” says Nixon, who is part of a team of researchers from CSIRO and the university’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience investigating the effect of venoms against parasitic worms.

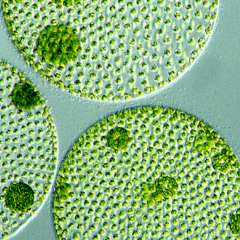

“Spiders are incredible animals – they have awesome, unique chemistries that have evolved over millions of years. Their venom has long been investigated for its medical potential in different fields, such as pain treatments and bioinsecticides. Applying it to parasites is a new approach.”

For a country with a sheep flock of around 68 million head and a sheep meat industry worth $5 billion, a breakthrough could be meaningful amid healthy demand. According to Meat & Livestock Australia, sheep and lamb prices this year are likely to average or exceed previous records due to tighter-supply.

MLA claims the US, China and the Middle East are Australia’s major sheep export markets, while the Australian domestic market share makes up around 46 per cent.

Nixon’s supervisor at University of Queensland began investigating venoms against parasitic worms around seven years ago.

After screening hundreds of different venoms, including from scorpions and centipedes, the team has found spider venom was particularly effective against parasites

For Nixon, who confesses she suffered from arachnophobia, it wasn’t entirely comfortable joining the team.

“I used to completely freeze with fear if there was a huntsman on the toilet door,” she says.

“Now having been around tarantulas and funnel webs in the lab, I can appreciate their fantastic characteristics and evolutionary adaptations. Let’s just say, I have developed a very healthy respect for them.”

Nixon says while the team’s findings are extremely promising, commercialising a parasite treatment could take up to a decade. Part of the problem is the lack of research funding compared to other research.

“Veterinary and tropical medicine research doesn’t have nearly the same visibility or funding of other fields, like cancer research, despite the importance,” she says.

“Given that sheep production is such a huge part of our economy, it’s disappointing that we’re not investing in these types of discoveries. It would have benefits well beyond the sheep industry – it’s equally applicable to cattle, lamas, goats – in fact, a huge portion of the world’s food supply.

“More investment in novel solutions is vital, or the impact of parasites to food supply will become dire.”

Nixon is determined to have a strong voice on this issue, with a view to speeding up the transition of her discoveries from the lab into the real world. To do so, when she’s not milking venom, a schedule of industry, academic and leadership events is helping her step closer to her goals.

Later this year, Nixon will head to China to attend the World Congress of Toxinology, and the Venoms to Drugs conference in her home state of Queensland, where she will collaborate with some of the leading venom researchers in the world.

Soon after, she’ll spend a month in Antarctica as one of 70 leading women working in STEM for the Homeward Bound leadership development course.

She is also working closely with a number of farming groups to help better manage drug-resistant parasites, until the venom solution becomes available.

“I've always been fascinated by how we can take things from the natural world and use them in biomedical and biotechnological applications,” she says.

“I’m also drawn to helping the people directly affected by problems, giving them a voice and helping to find a solution. I come from a family with a background in farming so, to me, this is a problem definitely worth solving. I can’t wait till we get this out into the field.”

Samantha Nixon was awarded a 2017 Westpac Future Leaders Scholarship, which is helping her to further her research career by supporting her participation in international congresses and leadership development programs. Applications for 2018 scholarships are currently open – until 5 September 2017.

Source: Emma Foster, Westpac Wire