Knowing the risk of excruciating pain that can last for days or weeks, yet daring to touch the Gympie Gympie tree, is precisely the fear our scientists push past as they dare to discover urgently needed new drugs and therapies.

The Gympie Gympie tree, native to Queensland and northern NSW, has become much more than just a bushwalker’s menace.

A research team at UQ are daring to believe that the toxins in this unique plant can lead to new pain treatments without the side effects or opioid dependency associated with conventional pain relievers.

New pain treatments a gamechanger

Giovanna Leung, a UQ parent and supporter to the Institute, shared her debilitating experience with chronic pain from a spinal condition called stenosis and is hopeful that this gamechanger research will help future pain sufferers.

“The pain is very difficult to describe, no one can really understand how it feels until they get it,” Giovanna said. “Being in pain is very very isolating. I don’t have the will to go and visit friends.

“There’s so much research that… I think people of my age in future are not going to have to go through the trauma… that I’m having to face right now.”

Dr Jennifer Deuis is part of a team that discovered that the neurotoxins responsible for the Gympie Gympie’s sting are more like the venom of spiders or cone snails than stinging nettles.

“It’s exciting because we found something that was not expected,” Dr Deuis said. “We found that a toxin in the plant was working on a new pain gene that had not been identified before.”

Toxin researchers dispel old myths

The toxins, named gympietides, are the focus of efforts to find better treatments for people that have been stung and, most importantly, possible breakthrough forms of pain relief medication.

Understanding how pain affects people and finding ways to relieve it has become a boom area of academic research.

But gympietides, which seem to have the ability to interfere with the nerve cells responsible for pain signals, have the potential to take such research to another level.

The researchers have also dispelled a myth about how to treat stings.

They’ve disproven previous belief that the pain from the sting is due to the plant’s fibres remaining on the skin, so no amount of applying wax strips to rip the fibres out is going to work.

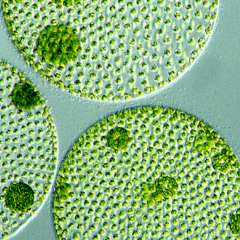

Instead, the fine hairs on the tree’s leaves, called trichomes, deliver the sting, acting like super-efficient hypodermic needles that inject toxins into the skin.

The work progresses despite the risks: Dr Deuis and her fellow plant-wranglers have had encounters with Gympie Gympie leaves that have proven too close for comfort.

“All of us have been stung,” she said, describing the pain as a “tingling sensation, sort of like an electric shock.”

For Dr Deuis, the risk of pain from the Gympie Gympie plant is worth it to help people with long-term chronic pain.

Researcher profile

Jennifer Deuis became interested in pain research after spending part of her career as a community pharmacist. The job ensured she met many people asking for pain medication that was more effective than what they were currently using. This led her to studying the toxins and venom created by a whole range of creatures that bite and sting, including spiders, ants and snakes. She says her ultimate aim is to find a drug “that relieves pain, has no side effects that can affect a person’s quality of life and is not addictive”.