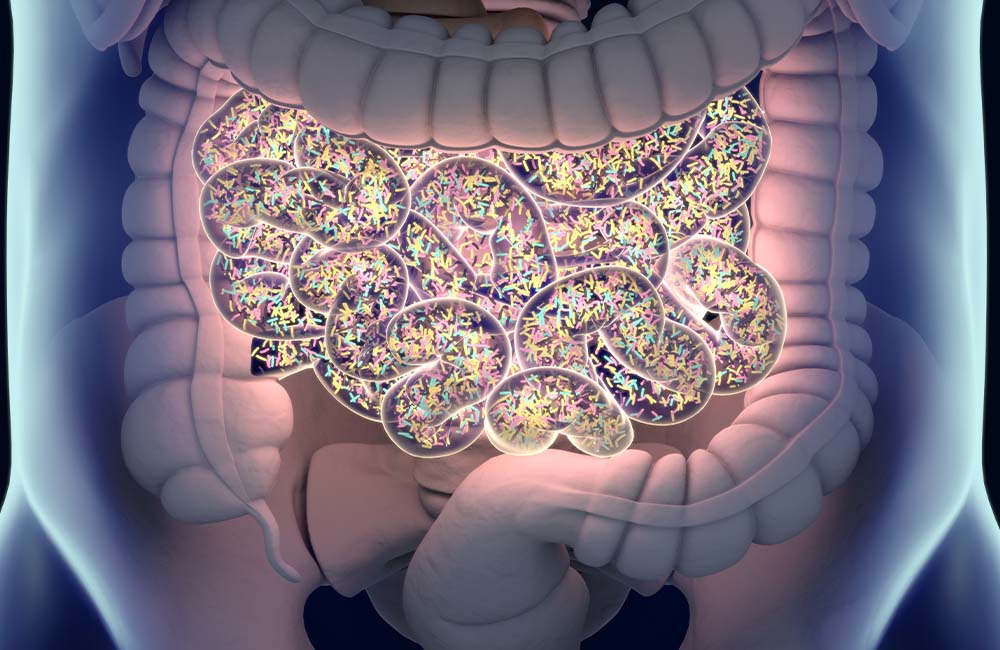

There is a growing interest in how our gut and the billions of bacteria that live in it – the microbiome – affect the rest of our body. But does all the advice on diet and disease stack up when put under the microscope?

Two IMB studies used genomics to debunk common myths around diet and disease.

Autism and microbiome

Picky eating has long been recognised as a symptom of autism spectrum disorder. Recent interest in the gut microbiome sparked the belief that this is because autism changes the make-up of the bacteria that live in the gut.

This belief has spawned a wealth of experimental treatments including faecal microbiota transplants and probiotics to attempt to change the gut microbiome and alleviate autism.

But do changes in our gut cause autism or does autism cause changes in our gut?

For her PhD research Dr Chloe Yap investigated the gut microbiome in children with autism and their siblings.

She analysed bacterial DNA from children’s stool samples and found there was no direct association between autism diagnosis and the microbiome composition but there was a correlation between a less diverse microbiome and diet.

“We concluded that children with an autism diagnosis tended to be pickier eaters, due to sensory sensitivities or restricted and repetitive interests which leads to a less diverse diet, reduced diversity in the microbiome and looser stools,” Dr Yap said.

“Our data suggest that behaviour and dietary preferences affect the microbiome, rather than the other way around.”

Fibre vs Genes

Diverticular disease of intestine (DivD) is a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease that, until now, was thought to be caused predominantly by a low-fibre diet.

PhD student Dr Yeda Wu was compelled to investigate the disease, fascinated that it is so common yet so overlooked.

Diverticula are sac-like protrusions in the wall of the intestinal tract affecting 33 percent of individuals aged 50 to 59, increasing to 71 per cent in those aged over 80.

.

"A quarter of people with diverticula develop symptoms and even complications such as abscesses and bleeding, which can be life-threatening," Dr Wu said.

“We were surprised to find that DivD is highly heritable, 40 per cent in fact, and our genome-wide association study of more than 700,000 people also identified 150 genetic factors linked to the risk of getting the disease.”

These genetic factors can be used to identify people who are at a higher risk of getting DivD so they can be monitored by their GP and encouraged to make changes to their diet to reduce the risk of developing the disease.

“While the genetics discovery is relevant for DivD treatment and prevention in the future, there is still a clear association between food intake and DivD,” Dr Wu said.

Studies like these also provide clues about how diseases are caused – some of the genes revealed were linked to colon structure, the layer of mucus in the gut and the processes that move food through the gut.