The ‘electric caterpillar’ is a public menace to gardeners in Townsville and the North-East of Australia but IMB researchers are looking beyond their painful stings to their potential as sources for new medicines and insecticides.

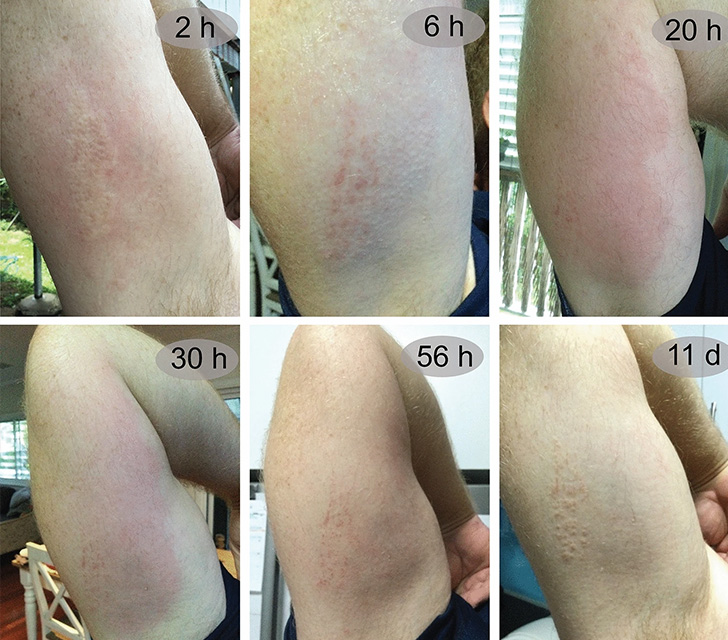

These beautifully coloured spiky specimens nestling on the lilly pilly tree cause a severe itch, sting or burning sensation with long-lasting lesions that can last for days with little relief from ice packs or the usual sting-relief gels.

IMB’s Dr Andrew Walker is a molecular entomologist with a particular interest in caterpillars and their venom.

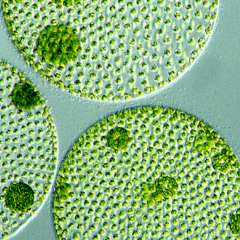

“All caterpillars do is eat and grow, and they don’t move very fast, so are very vulnerable to predation – their defence mechanisms include camouflage, irritative hairs, and venom-injecting spines.”

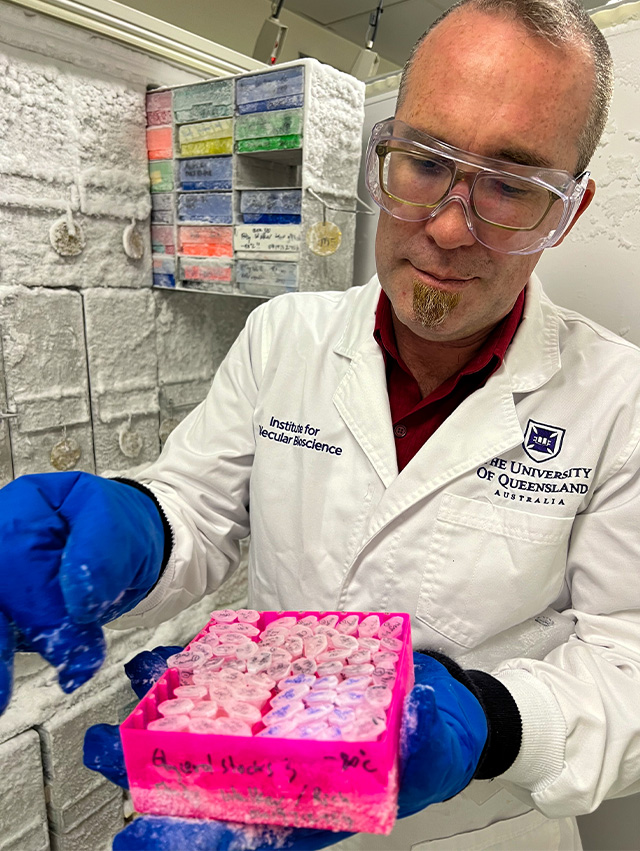

IMB has the largest invertebrate venom library in the world and a proportion of the library’s freezers are filled with caterpillar venoms as Dr Walker continues his exploration of how venom evolved in caterpillars.

Tracking down the electric caterpillar

“We heard about this caterpillar with a ferocious sting and were keen to test its venom, so went up to Townsville to find one – it hangs out on lilly pillies, so we looked in any lilly pilly we came across,” Dr Walker said.

“After a couple of days of no luck, we put a message on some community gardening discussion boards, and received an outpouring of stories of the extreme pain and hospital visits these caterpillars have caused.”

After finally finding a caterpillar to take back to the labs at IMB, Dr Walker was surprised to find that the venom was similar to that produced by a family of American insects called asp caterpillars, which are also known for their painful stings.

“It’s a really different composition to the venoms produced by the other species in this family we have studied so far, which provides exciting possibilities for finding useful molecules in the venom that we can use in other ways” Dr Walker said.

Linking the caterpillar to the moth

The researchers also ‘barcoded’ the caterpillar’s DNA to fully identify it, discovering it is the caterpillar of the inoffensive Comana monomorpha moth.

“Just about anywhere, including Australia, caterpillars are poorly identified. Often, no one knows which caterpillar matches which butterfly or moth – it's partly because of the huge diversity of insects and other animals, but also much of our biodiversity remains unexplored.”

But now, DNA databases help in the identification process, including for those working to unravel how venoms evolved in caterpillars.

Evolution of venom

“This ‘electric’ caterpillar has caused us to revise our theories of how venom evolved – it belongs to the Limacodidae family (nettle or cup moth caterpillars) but has venom more similar to the Megalopyge family (asp or puss caterpillars),” Dr Walker said.

“We think all caterpillars descended from a common venomous ancestor but as they diverged, some lost their venom and some kept the ancestral form, whilst others evolved venoms with different compositions.”

Using venom for good

Dr Walker and the team are now exploring the venom they’ve collected and working out the functions of the molecules inside and how they can be used for good.

“Some of the venom molecules have insecticidal properties, so we are looking at them for use as pesticides, and others can activate receptors in the human body, so could potentially be used in medicine or for scientific tools.”

But if someone turns up with a new unidentified caterpillar?

“I'm very excited to be doing science and looking at these amazing animals, so it’s hard to say no and I’ll continue to be fascinated by the evolution of their different venoms.”

The research team included IMB’s Mohaddeseh Goudarzi, Dr Samuel Robinson, Dr Fernanda Cardoso, Professor Glenn King, Associate Professor Lyn Cook from UQ’s School of the Environment and Dr Michela Mitchell from the Department of Toxinology, Women’s and Children’s Health Network.

This research was published in the Nature family journal Scientific Reports.