The assassin bug lies in wait in plants, poised to ambush its prey. Related to cicadas and aphids, it has a large appetite, catching any unsuspecting invertebrates, like caterpillars or bees, for its next meal.

A seasoned killer

Using its needle-like mouthparts to pump venom into its prey to paralyse them, the assassin bug then liquefies the body and sucks its already-digested meal up through its proboscis, like a straw.

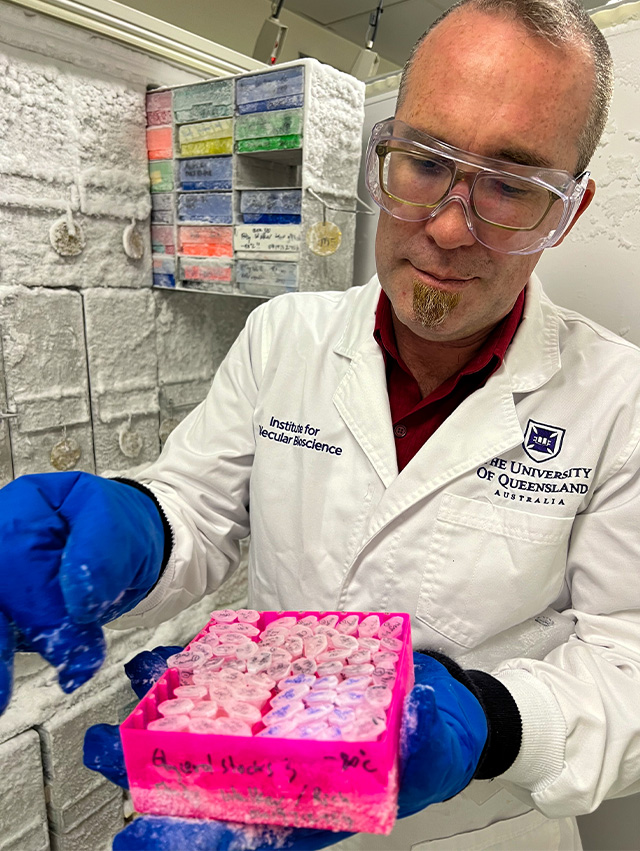

Researchers at IMB are harvesting assassin bug venom to explore its fascinating properties.

An untapped source of insecticides

Dr Andrew Walker, one of IMB’s molecular entomologists, said assassin bugs are a great source of new insecticidal molecules because they have evolved for millions of years to kill insects.

“We are looking to nature for natural bioinsecticides, to find safer alternatives to their chemical counterparts.”

In previous research, Dr Walker found that assassin bugs make two kinds of venom – one to hunt their prey and another to defend themselves against predators.

Double the venom

Double the venom means double the scope for finding a molecule that does the job – the hunt is on at IMB to find eco-friendly insecticides to join the ones already found from spider venom.

The researchers use magnetic resonance experiments to solve the detailed three-dimensional structure of the peptides in the venom, which offers clues to their function.

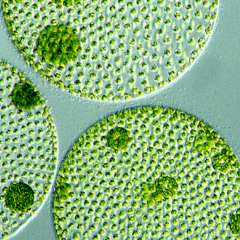

“We recently found a peptide – a small protein – called Pp19 from the assassin bug Pristhesancus plagipennis – this peptide looked interesting as its structure was unlike any previously isolated from an insect,” Dr Walker said.

A structure for defence

“We found that it folds up into a structure eerily similar to a peptide produced in humans called alpha-defensin.

“Alpha-defensin is found in mammals and is part of the immune system, killing bacteria, fungi and viruses.”

“Mammalian alpha-defensin and Pp19 from the assassin bug are both examples of a structure we call a “trans-defensin” – although we commonly see these molecules in mammals, it’s the first one of its type that has been seen in insects and may have been recruited into venom due to its insecticidal properties.”

Expanding the sphere of knowledge

The study is part of a broader program at IMB to identify new molecules from Australian flora and fauna that can have a positive impact on health and the environment.

“Animals like scorpions and spiders are known to make insecticidal peptides and we are very excited about the possibility of using these to make better insecticides,” Dr Walker said.

“But there are plenty of other groups of venomous arthropods whose venom might contain useful molecules, and for many of these their venom has never been studied – we’re trying to expand that sphere of knowledge”.

The research was published in Structure.

The research team included IMB’s Dr Yanni Chin, Dr Shaodong Guo, Jiayi Jin, Evienne Wilbrink, Deseh Goudarzi, Hayden Wirth and Professor Glenn King.