Professor Ian Henderson may be a researcher in science, but it was a knowledge of history that inspired him to study some of the world’s smallest living organisms.

The new Director of IMB has devoted his working life to studying antibiotic resistance – the ability of microbes to resist treatment – and develop solutions to this urgent global challenge.

]

How history and microbes shape our world

Professor Henderson, who is Irish born and bred, says he has always been fascinated by how decisions in history shape the world in which we live today.

“Growing up in Ireland, the microbe that stands out most in the school curriculum is the one that caused potato blight, which directly led to the Irish famine. This event had a massive impact on Irish society, causing mass deaths and emigration, depleting ¾ of the population, and it was all caused by a tiny organism – this really drove my interest in microbes.

“But microbes aren’t a historical footnote. I think people forget, or don’t know, the impact that microbes continue to have in all sorts of diseases: communicable, the infections that we normally associate with microbes, but also non-communicable disease. Microbes play a role in diabetes, cancer, causing stroke and heart attacks – this is not really recognised by the public or even by some of our peers.”

As with many scientists, a teacher also played a role in Professor Henderson’s choice of career.

“I had a high school biology teacher who was also a postdoc at Trinity College in Dublin. Because she was a researcher, she was able to share much more detail about biology than was in our textbooks. Being able to converse with someone at the coalface of research sparked my interest in science and scientific research.”

Professor Henderson went on to undertake a PhD at Trinity College in medical microbiology and bacteriology.

Is the surface of bacteria key to treatments?

Professor Henderson’s research is focused on solving the problem of infection.

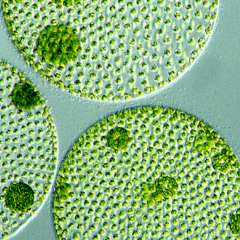

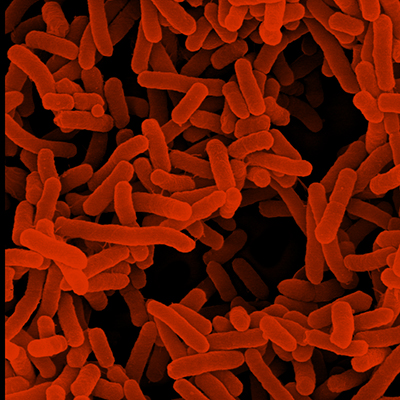

“All cells, including bacteria, have a surface, and the structure of this surface is crucial to how they interact with their environment.

“If we can understand the relationship between the surface of a bacterial cell and its environment, then we can disrupt those interactions and stop infection, and the negative consequences of coming into contact with some micro-organisms.”

The passion that Professor Henderson holds for his work is underscored by the urgency of our need for better treatments for diseases caused by microbes.

An oft-quoted stat is that, if we don’t take action and develop new strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance, 10 million people per year will die of drug-resistant infections by 2050; that is in addition to the 12 million that die each year of drug sensitive infections.

The UN report behind this statistic also warns that antimicrobial resistance could force 24 million people into extreme poverty by 2030 – a mere decade away.

It was the challenge of overcoming this pressing global issue that saw Professor Henderson make a move to the other side of the world.

IMB a world leader in antimicrobial research

Following his PhD, Professor Henderson worked across four countries and three continents – but these different locations all had one thing in common.

Positions in Baltimore, Belfast and Birmingham made Brisbane seem like an inevitable choice. But it was ultimately the possibility of helping people that drew Professor Henderson to the southern hemisphere.

“I had set up a centre in Birmingham to combat antimicrobial organisms but we didn’t have a vehicle for translating that work into patients. The University of Queensland, as far as I could establish, is the number one university in the world for antimicrobial research and actually getting the work from the basics through into patients.

“UQ has people like Rob Capon and Mark Blaskovich doing chemical discovery, and David Paterson and Jason Roberts running clinical trials in the antimicrobial space. So I saw a route for some of our work to make it through the valley of death – the gap between a promising discovery and translation into a treatment – into people who urgently needed positive outcomes for their infection. Since I arrived we have successfully implemented our new treatment in one patient and so the future looks bright”

“Australia in general has an amazing international reputation for producing high-quality work in the field of microbiology. I think it’s awesome and I’d love to engage more with people around the country.”

The icing on the cake for a move Down Under?

“Of course, there’s also the awesome weather and the amazing people!”

The history and future of IMB

Professor Henderson began at IMB in 2018 as the Deputy Director of Research, working under the former Director, Professor Brandon Wainwright.

“I can’t understate how much IMB owes to Brandon,” Professor Henderson says. “He became Director at a time when funding was plentiful and secure, and has navigated the institute through the choppy waters that followed, as competition for funding greatly increased.

“The fact that IMB research outputs continued to grow in both quantity and quality is a testament to his incredible leadership for over a decade.”

Now, as IMB enters its 20th year, it’s Professor Henderson’s turn to steer the ship. When asked what he thinks the Institute’s greatest strength and challenge are, he gives the same answer.

“Its greatest strength is the diversity of the science.”

“Our research is predominantly fundamental, underpinning our knowledge of biology, but spans from the fundamental to drugs for infection, stroke and arthritis”

“It’s all fascinating and it’s all exceptionally high-quality and leading-edge research. Our challenge is to ensure we can deliver positive impact to our local and wider community and to articulate what we are trying to achieve for society.”

“But the potential within IMB to harness the chemistry, biology and genetics expertise to make a difference is enormous. There are few places in the world where you have access to all the necessary equipment to do that type of research within a single building, while having the depth and excellence of colleagues across the campus.”

“It is clearly one of the strongest research institutes worldwide, and certainly in Australia, and I want it to be known for that on a global platform.”

When asked what he misses about the United Kingdom and Ireland, Professor Henderson looks pensive.

“You miss people,” he says. “You miss family, friends and colleagues. It’s a long way to everywhere, but the benefit is everyone wants to visit”

“But other than that, I’m very happy to be here!”