Linlin Ma, The University of Queensland and Glenn King, The University of Queensland

A little baby suffering a seizure is an incredibly distressing event for a family. Epilepsy is the most common neurological disorder in children and it takes the form of recurring seizures. But epilepsy is not a single disease; rather, it is a diverse spectrum of disorders that comprise many types of seizures.

Dravet syndrome, first identified by French psychiatrist and epileptologist Charlotte Dravet more than 30 years ago, is a severe paediatric epilepsy.

Dravet syndrome (previously known as severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy) starts in early infancy and evolves through different stages to adulthood. It is a rare disease, with an incidence of about 1.4% in epilepsies of children younger than 15 years (about 1% of the total global population have epilepsy – about 65 million).

Babies with Dravet syndrome appear normal during the first few months after birth, but typically have their first seizures at five to eight months of age. Subsequently, patients often experience multiple types of seizures. These seizures are particularly difficult because they are frequent, unpredictable and resistant to many anti-epileptic drugs.

Within the second year of life, there are delays in behavioural and other development, mild to severe mental retardation, sleep disturbances and personality disorders (such as social isolation, frequent mood swings). Dravet syndrome is also associated with increased risk of sudden death.

Genetic cause

The most significant advance in understanding the cause of Dravet syndrome was the discovery of its genetic background. In 2001, mutations in a gene known as SCN1A were identified in seven children with Dravet syndrome.

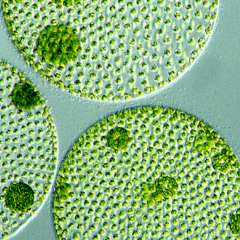

Subsequent genetic studies revealed about 80% of patients with Dravet syndrome carry a mutation in this gene, which produces a protein called Nav1.1. This protein helps generate and transmit the electrical signals that cells of the nervous system use for communicating with one another. Mutations found in the SCN1A gene in Dravet syndrome patients cause Nav1.1 to malfunction.

In the brain, Nav1.1 exists predominantly in a group of neurons that are responsible for calming brain activity. A malfunction in Nav1.1 inhibits that calming ability, leading to seizures.

The brain begins producing Nav1.1 in the weeks following birth, with production increasing as a baby ages. This may explain why Dravet syndrome does not become apparent until five to eight months after birth.

What we can do

Dravet syndrome is incurable and has a significant impact on the development of affected children. As for any other chronic condition, the primary goal is to ensure the best life quality for patients and their families.

The progressive and unpredictable course of Dravet syndrome can cause extreme anxiety for the families of affected children. Early diagnosis is critical to avoid inappropriate treatment and enable timely provision of counselling, rehabilitation and psychological support.

There are drugs to help reduce the frequency and severity of seizures. These include benzodiazepines, valproate, topiramate and stiripentol.

A high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet could be considered if anti-epileptic drugs fail to provide seizure control. Overheating is the most frequent seizure trigger in children with Dravet syndrome. Therefore, conditions that might cause hyperthermia – such as summer sun, physical exertion, or a hot bath – should be avoided.

Seizures can also be induced by stressful situations. A general rule of thumb is to keep the optimal balance between seizure reduction, drug load and side effects, while avoiding the use of too many medications.

A child with Dravet syndrome is at risk of developing cognitive and physical deficits but it is possible to minimize these with appropriate medication and by offering appropriate educational and rehabilitative opportunities, such as speech and occupational therapies.

Management of behavioural disturbances is not easy, so families should seek as much support as possible from medical staff and support organisations such as the Dravet Foundation and Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy.

Future prospects

Despite more than 30 years of research, Dravet syndrome remains a difficult-to-treat epileptic disorder with a major impact on affected children and their families. However, during later life, seizure control generally improves, so prevention of severe seizures in young patients should improve prognosis.

Fortunately, major developments in our understanding of the genetic cause of Dravet syndrome have paved the way for more suitable treatments and the prospect of precision drugs that directly target the root cause of the disorder.

![]() The development of medicines aimed at boosting the function of Nav1.1 in patients with SCN1A mutations is a new and promising direction in Dravet syndrome therapy. These drugs will not only help prevent seizures but might also begin to reverse some of the developmental delays associated with this disorder.

The development of medicines aimed at boosting the function of Nav1.1 in patients with SCN1A mutations is a new and promising direction in Dravet syndrome therapy. These drugs will not only help prevent seizures but might also begin to reverse some of the developmental delays associated with this disorder.

Linlin Ma, NHMRC CJ Martin Fellow, King Group, Division of Chemistry & Structural Biology, Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland and Glenn King, NHMRC Principal Research Fellow, Professor, and Group Leader, Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Main image Severe seizures in young children can be terrifying, but they can be managed. Alex Proimos/Flickr, CC BY-SA