Imagine a world in which a simple scratch could kill you. It may sound unfathomable, but this was reality before the development of antibiotics in the mid-20th century.

Prior to the invention of these lifesaving drugs, over half of all deaths were due to infections, such as pneumonia and tuberculosis.

Before antibiotics, a scratch could be deadly

A scratch or wound could ultimately lead to your death if it allowed disease-causing bacteria to enter your body.

Antibiotics, which kill bacteria and other microbes, allowed us to recover from these infections and helped to increase average life expectancy in the developed world by decades.

Developing resistance to antibiotics is a natural phenomenon found in ancient bacterial DNA from 30,000-year-old permafrosts.

Bacteria are an ever-evolving foe, with the ability to build up resistance to antibiotic drugs, rendering them ineffectual.

These “wonder drugs” have been prescribed inappropriately too many times, helping bacteria develop resistance.

Exacerbating the situation is the lack of development of new antibiotics – in the past few decades most pharmaceutical companies have ended their programs.

We are facing a return to the pre-antibiotic era

This leaves us, less than a century since the first antibiotic came onto the market, facing a return to the pre-antibiotic era.

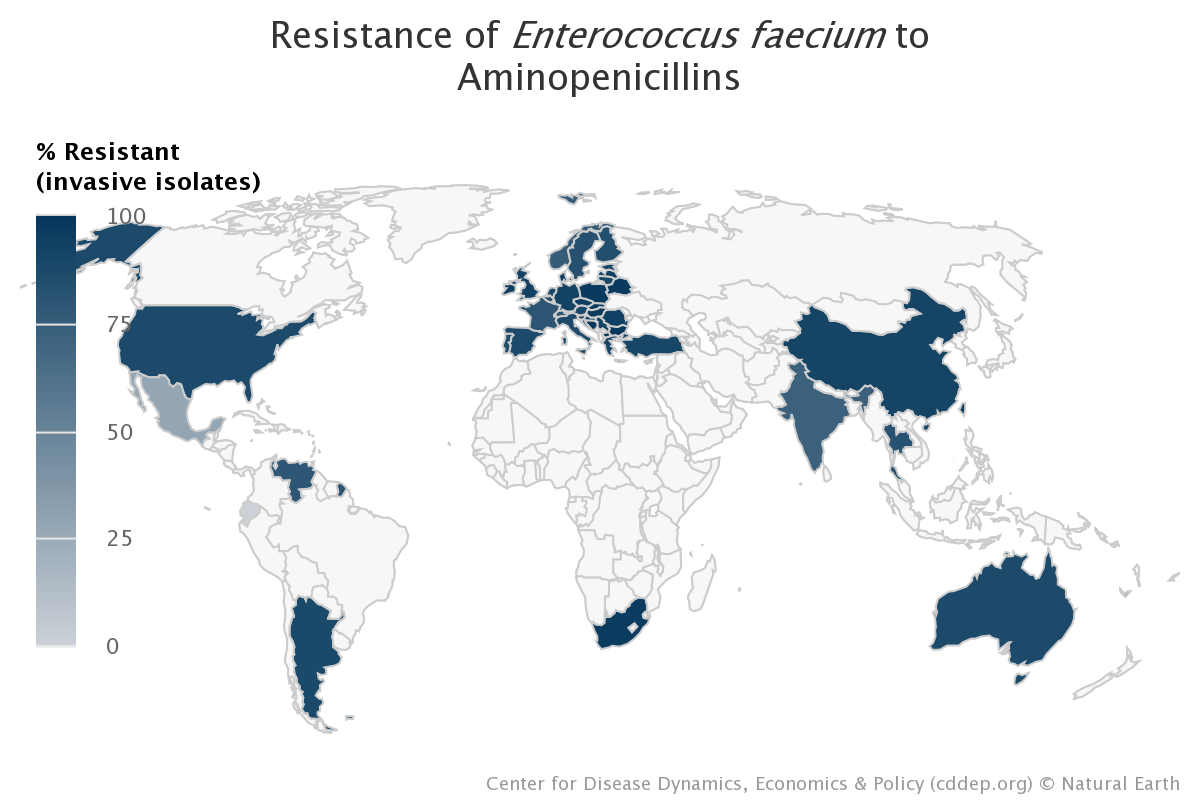

In 2019, the most recent year for which we have comprehensive statistics, nearly 5 million deaths worldwide were associated with drug-resistant bacterial infections.

BY THE NUMBERS

Deaths worldwide associated with

drug-resistance bacterial infection

4.96m

The highest burden is in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, but all regions of the globe showed resistance, making it a major cause of death globally.

If we can’t find a solution to the rise of superbugs, we could revert to the life our ancestors led, where dental surgery can be fatal; you risk losing your leg because of a simple scratch while gardening; and the chance of infection during a cancer treatment or hip replacement makes them too risky to contemplate.

IMB researchers are fighting back

The number of people dying is a grim reminder of how formidable superbugs are.

But our researchers are teaming with colleagues from across the world to fight back, and you can play your part too.

Read The Edge: Infection to learn more about bacteria, the changes we can each make, and how research is offering hope for the future.

How do bacteria infect us – and how do we fight back?

Our bodies are normally very good at keeping bacteria where they generally don’t cause damage – on skin surfaces and in the digestive tract – and away from areas that should be “sterile” – such as the urinary tract or blood.

Mostly this is done by using barriers that physically prevent the entry of bacteria.

But every so often bacteria make it through.

The body then relies on a variety of internal defences to identify, isolate and deactivate the invading bacteria.

Bacterial infections occur when one of these mechanisms is breached.

Physical damage to the skin, such as cuts and scrapes, or surgery, can allow bacteria ready access to the inside of the body, potentially introducing more bacteria than the body’s defence systems can handle.

Immunocompromised patients, such as those with organ transplants or undergoing cancer treatments, are more susceptible to infection because the body is less able to keep small numbers of invading bacteria or fungi at bay.

What are bacteria?

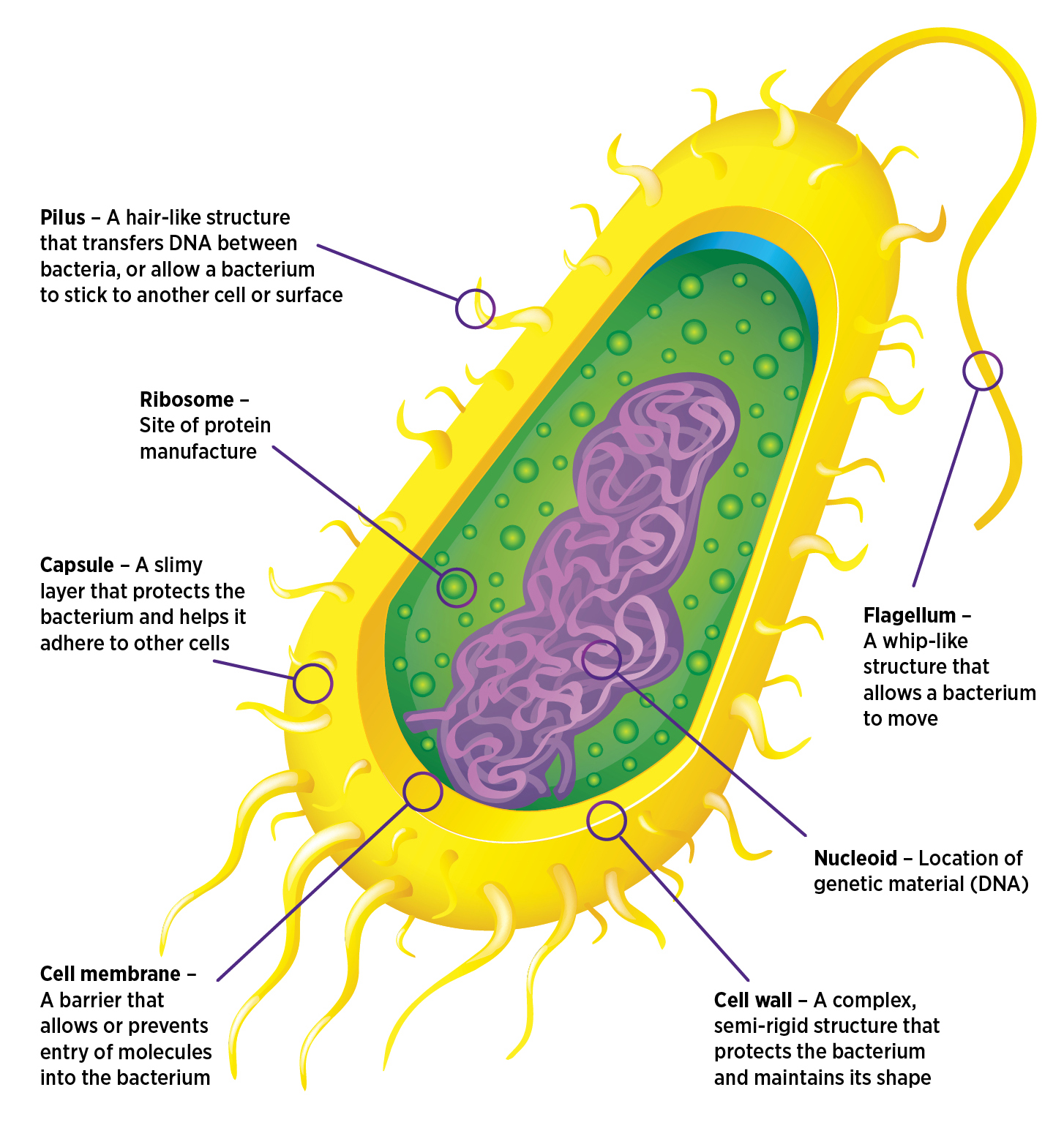

Bacteria are prokaryotes – the smallest, simplest and most ancient cells, with free-floating genetic material.

These microscopic organisms can be rod, spiral or spherical in shape.

Bacteria can communicate with one another by releasing chemical signalling molecules, allowing the population to act as one multicellular organism.

This is a powerful weapon against antibiotics, allowing some bacteria to become dormant when exposed to an antibiotic, then regenerate when it is gone.

What is antibiotic resistance?

Resistance occurs when bacteria survive and continue to cause disease even after an infected person has taken antibiotics.

Antibiotic resistance is not the patient becoming resistant to antibiotics, but the bacteria becoming resistant.

Bacteria reproduce quickly and can share DNA between themselves, rapidly adapting and changing over time to outwit antibiotics.

What are superbugs?

Superbugs are bacteria that are resistant to more than one antibiotic, which makes them exceptionally dangerous, especially those that are resistant to all antibiotics.