Know your enemy! That’s the approach immunologist Dr Larisa Labzin applies to her work at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience. And, since early this year, the adversary she’s been intimately acquainting herself with has been the virus that causes COVID-19.

By understanding how the body responds to a COVID-19 infection – when the virus breaches our body, starts replicating and spreads through the bloodstream – she’s hoping to identify where the disease can be stopped in its tracks. And to do that she’s been delving deep into the molecular level where the virus operates, wreaking its havoc.

Dr Labzin’s particular area of expertise is the innate immune system – the body’s first line of defence against invading organisms, such as viruses and bacteria. That’s where alarm bells first go off that a pathogen is travelling through our bloodstream and targeting our cells, which in the case of the COVID virus are mostly those of the lungs. And it’s been there, in the innate immune system, where the COVID-19 virus has been proving to be such a difficult foe to fathom. Importantly, in the absence of a vaccine, it’s also the place where we have the best chance to fight the disease.

Molecular messengers and detectives

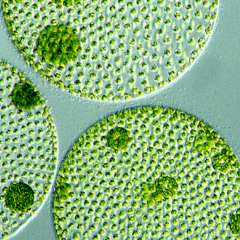

It’s normal for our innate immune system to react to an invading organism by raising an army of white blood cells called macrophages – a response known medically as ‘inflammation’. One of the early actions of macrophages is to sound a kind of clarion call throughout the body via the release of an array of proteins called cytokines. These are messengers that race through the body, assess infection and send feedback about how and to what extent the body needs to respond.

Dr Labzin’s research investigates the various molecular players involved in inflammation. “I study what that whole process looks like after the white blood cells appear and I think of them like the police arriving after someone has broken into your house,” she explains. “They’re looking for clues as to what kind of intruder it might be, especially if they have already moved on.”

The immune system needs to first determine whether it’s a virus that it needs to respond to and then which one, because it has to mount a different response to a seasonal flu virus, for example, than to the COVID virus. “The innate immune system can detect signs without necessarily knowing what is, or has been, there,” Dr Labzin says. “So, I really do think of these cells like they’re police trying to work a profile, picking up various clues as to who the perpetrator might be.”

Our own worst enemy

But what happens in severe cases of COVID-19 is that these cells – these molecular detectives of the innate immune system – aren’t working properly. They detect some part of the COVID-19 virus, or damage to other lung cells caused by the virus, and overreact in an unhelpful way. Then it’s like trying to put out fire with more fire: as those macrophages keep trying to solve the problem with more cytokines, more macrophages come in, try to fight, get it wrong and release more cytokines. The result is a cytokine storm.

“So, when that gets out of control or that signal constantly keeps getting sent, that’s when we start getting a lot of damage and sickness,” Dr Labzin says. “And that’s because these immune cells are pretty powerful and as they go all out to try and kill the virus it often includes taking out some of your own cells as well, which can cause a lot of damage.”

It explains what’s often seen in adults with COVID-19, particularly elderly patients – a very strong hyperinflammatory response. “So, even when tests show virus levels are dropping or very low in a patient’s blood, they can be very sick because the immune response is so high and has kind of stormed out of control, causing really severe damage,” Dr Labzin says.

“This has been confirmed by the success of dexamethasone (an immune suppressant) in treating patients seriously ill with COVID-19. By the time they are hospitalised the damage is being caused by the immune system, not the virus, and we want to understand why that’s happening,” she adds.

Strange symptoms in children

Outside Australia, in populations with high levels of COVID infection there are reports that a growing number of children who come in contact with the virus are presenting with what seems to be a dangerous immune response. Unlike adults, children often show no signs of an initial COVID-19 infection. But what paediatricians in London and New York, for example, are seeing amid the pandemic is a rise in children presenting with a range of symptoms reminiscent of a rare childhood illness called Kawasaki Disease. These include a rash, long-lasting fever, swollen lymph nodes, conjunctivitis and, in severe cases, inflammation of the heart.

Kawasaki Disease is usually seen in children below the age of five years. But this illness, which seems to be linked to the pandemic, is being seen in children aged up to about 15.

They usually have no active virus in their blood, but there are signs COVID has been there. “It looks like the virus triggers something in the immune system and then we are getting this Kawasaki-like disease – a hyperinflammatory response,” Dr Labzin says. “So, in normal healthy adults or children, the immune system would be like, ‘Oh, there’s something here but actually it’s not that dangerous, so it just needs a tiny response and then we can just get back to normal.’ But what’s happening in the really sick patients is their immune system is seeing a small threat and thinking it’s much bigger than it actually is and then mounting a full-on response.”

So, if we knew what it is about the COVID-19 virus that triggers and confuses the signals in the innate immune system driving inflammation, it should be possible to find ways to block it and prevent the disease from becoming deadly.

And that is exactly what Dr Labzin is hoping to find.