How the Butterfly Pea gave rise to a world first for natural insecticide.

Across the world, farmers utilize insecticides to protect crops. But there is growing concern that the chemicals sprayed on our food could be damaging to our health, as well as the health of the world’s crop pollinators – bees.

The current trend in healthy eating is to eat ‘clean’ with demand for organic produce on the rise. And colony collapse disorder (in bees) has become an issue of global significance. But populations and demand for food are increasing, and organic farming can result in significant loss of yields to pests. Loss of crops increases the cost to farmers and therefore consumers. So farmers have had little choice but to use synthetic insecticides, until now.

An Australian family owned research and development company based in Wee Waa NSW, Growth Agriculture, has found a solution. With the help of researchers at the University of Queensland’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience, and funding from local cotton growers, they have created the first mass-producible organic insecticide from peptides found in a plant called the Butterfly Pea.

The Butterfly Pea – and the search to unlock her secrets

In the 1960s, around the time that Rachael Carson published Silent Spring criticising the indiscriminate use of chemicals, Kerry Watts got his first job in agriculture. Uncomfortable with the farming practices he witnessed, he set about finding natural alternatives. In 1992 Growth Agriculture was established to manufacture and distribute niche organic agricultural products.

While his son and co-Director Nick says he would hate to be called a visionary, his commitment to being involved in the development of such a revolutionary product as Sero-X suggests Kerry Watts is exactly that.

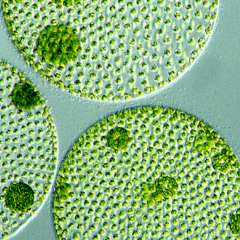

The Butterfly Pea, or Clitoria ternatea, has been used for hundreds of years for a variety of medicinal applications. But most importantly, insects don't eat the plant. Dr Robert Mensah from New South Wales Department of Primary Industries was working with the Cotton Catchment Communities CRC to find out why. He approached Nick and Kerry Watts to partner in the project. They could see the potential for a natural insecticide and so co-funded the project. At the end of the project they were convinced they had a natural insecticide, but needed further research to get it to market. The local cotton growers agreed. They created Innovate Ag to continue the research.

“We were trying to create a natural insecticide from the plant, but we didn’t know how it worked. We needed to uncover the active ingredient,” said Nick.

The secrets of the plant were proving hard to illuminate until a researcher working on the project attended a conference on the other side of the world. He saw UQ’s Professor David Craik present on a family of plant proteins called cyclotides, and he wondered could cyclotides be the active ingredient?

“Cyclotides are a protein with a uniquely stable circular structure that plants make to protect themselves against insects,” said Professor Craik.

Professor Craik discovered cyclotides in the 1990’s and is the leading authority on the uniquely structured proteins.

"I have been studying cyclotides as a tool for drug design for 15-20 years. After presenting on the topic, I was approached with the problem of the Butterfly Pea."

Professor Craik met with Innovate Ag and applied for an Australian Research Council Linkage Grant to evaluate the active properties in the Butterfly Pea, which was found to be a cyclotide.

Having identified the active ingredient and determined how to extract it, optimize its yield and determine its safety, Innovate Ag were able to develop Sero-X, the world’s first mass-producible organic insecticide based on peptides.

Creating the world’s first organic insecticide: Sero-X

Sero-X has been approved for both cotton and macadamia crops in Australia, and a partnership deal has already been signed with a multinational company based in Europe – Bi-PA. Bi-PA specialises in bringing biological products to market all over the world, so we could soon see the product used more widely across the globe.

“Until now organic farmers had very few options to protect their crops. Without synthetic chemicals, it was difficult to produce food that looked the way the market wanted it, and they also suffered reductions in yield. For example, macadamia growers can lose up to 80% of their crop from the fruit-spotting bug,” said Nick.

"Low yields are why organic produce is more expensive. But with an organic insecticide, producers can grow fruit that looks great, and they don’t have to sacrifice yield or quality.

“Sero-X is also very favourable on price to chemical alternatives,” said Nick. “So we hope that Sero-X will revolutionise agriculture and the price of organic produce may begin to fall.”

The other benefit of a natural insecticide is the impact on non-target organisms, like bees.

“The decline of bee populations has risen to be an issue of international concern. One potential culprit is neonicotinoids found in chemical insecticides.

Bees collect neonicotinoids from crops that have been sprayed and ferry it back to their colony. When it reaches a critical mass, it wipes out the whole colony,” said Nick.

In contrast, the organic insecticide derived from Butterfly Pea breaks down into biodegradable amino acids and so has minimal environmental impact.

Professor Craik continues to work on the project, exploring ways to synthesise the protein for scale and improve the extraction procedure to access more of the active ingredient. They are also exploring which pests the insecticide will be active against more broadly.