A soil sample is not your typical souvenir and Dr Zeinab Khalil is not your regular tourist.

She sees the landscape differently, delving deeper, looking at the texture of varied terrain, scouring remote regions and venturing to rare mineral-rich areas to synthesise the secrets of the natural world and unlock their medical benefits.

On her travels around Australia, she has collected 350 soil samples from an array of locations in the hope of discovering new medicines derived from nature.

It’s the organic evolution from a pivotal childhood moment when Dr Khalil was eight. Her father, a doctor, explained that a patient she encountered had died of a multi-drug-resistant bacterial infection.

It set Dr Khalil on a determined path away from studying medicine, where she would treat one patient at a time, to study pharmacy and pursue a career analysing the effects of bacterial infection on the immune system to uncover new treatments against antibiotic-resistant infections, known as superbugs – a mission that could see her save countless lives with her discoveries.

The lore of the land

As Director of Soils for Science, a ground-breaking Australian-first citizen science project, the IMB Australian Research Council Future Fellow probes the hidden world of microbes in soil samples sent for analysis from around Australia.

“The majority of antibiotics currently available are derived and isolated from microbes present in the soil, but none have come from Australia,” Dr Khalil said.

“Australia is such a large landmass, covering roughly two million square kilometres with a natural environment that is among the most biodiverse in the world.

“However, it remains a completely untapped source of potential drug leads. No one has looked at Australia in this way before.

“So, why don’t we go back to our soil, study it in depth and try to uncover new microbes with the capability to fight antibiotic-resistant infections?

“Soils for Science is the only initiative exploring and analysing microbial diversity on this scale so every sample is a great adventure for us.”

Since the project launched in January 2021, the Soils for Science team has received 11,000 soil samples, identifying 41 molecules that killed drug-resistant bacteria and uncovering 20 previously unreported molecules.

Dr Khalil and her team analyse the soil to discover, cultivate and catalogue the unique microbial collection in each sample to harvest new antibiotic leads.

Translating nature’s secrets

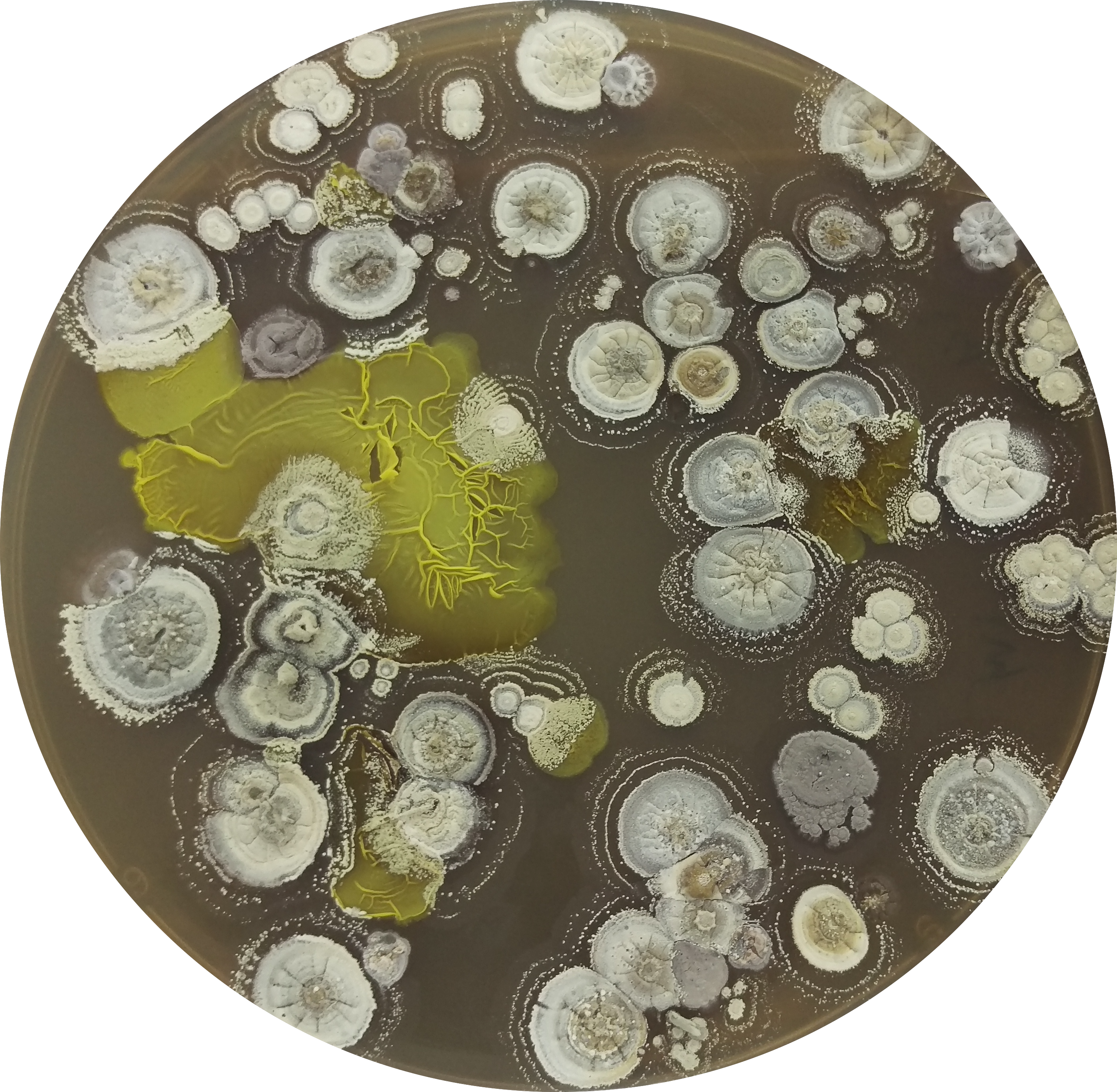

Under the microscope, these microbial cultures are storytellers, weaving tales of epic battles between bacteria and fungi over territory played out in miniature that allow scientists such as Dr Khalil to unearth insights into the inner workings of nature.

Bacteria and fungi deploy an arsenal of chemical weaponry when fighting over territory, trying to impede and destroy each other.

Within these microscopic defence mechanisms are the hidden secrets of nature IMB researchers want to unlock and use to develop new antibiotics.

The ‘zone of inhibition’, a circular area that forms around an antibiotic strain where competing microbes cannot grow, predicts its potential for antifungal or antibacterial properties.

The cultures are often beautiful canvases with intriguing shapes and colours as the bacteria and fungi present in the petri dish reveal clues for scientists to uncover.

Bacteria can be round (cocci), spiral (spirillum and spirochetes) or (rod-shaped bacillus), while fungi have varying forms, mostly thread-like hyphae.

Dr Khalil said one soil sample yielded floral shapes with a vibrant purple hue reminiscent of The University of Queensland’s iconic jacarandas.

A new chapter

But the spotlight is not only on soil for drug leads. Dr Khalil’s current research includes the search for new molecules to treat Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD) and control the pain and treatment of epilepsy.

Other projects in the pipeline are looking at new-generation antiparasitics to protect livestock from parasite infections and antifungal treatments to shield plants, such as avocados and strawberries, from fungal infections that have grown resistant to widespread methods.

Collaborating with clinical colleagues from UQ, Dr Khalil and her team can test new molecules against nasty pathogens, such as sepsis, isolated from patients.

“We are looking for new cures everywhere. Everything from nature is useful,” Dr Khalil said.

“Finding a molecule that is actively resistant to bacteria is exciting because it is very hard to discover chemistry that can inhibit the growth of superbugs.

“When we perform the chemical analysis, and discover the inhibition activity derived from a new molecule that has not been discovered, we are super happy and jump around the lab.

“It could be the next wave of new antibiotics in the war against superbugs and hope for future generations – all from the land.”