Discovering the genes involved in a disease is vitally important for our understanding and designing treatments. But it’s not the whole story.

IMB’s Dr Brett McKinnon works on the genetics of endometriosis, and explains how to make the leap between knowing the genes involved in a disease and teasing out their function to ultimately impact treatment.

“Our lab contributed to a genome-wide association study for endometriosis and found 42 genetic regions associated with the disease,” Dr McKinnon says.

“The next step for us is to look at how these genetic regions can influence gene expression, in other words, which genes are turned on or off in specific cells.”

Every cell in our body has a copy of our genome, each containing the same genetic information. The reason heart cells are different from skin cells, for example, is down to the genes a cell turns on or off, which trigger instructions to produce different proteins and give the cell its unique function.

“Examining gene expression is a direct link between our genes and the function of the cells,” Dr McKinnon says.

Mutations offer crucial clues

Mutations in gene regions associated with disease can offer crucial clues as to which genes are affected, and which functions are altered as a result of the mutation.

“Because of DNA’s coiled structure, a mutation may affect a gene quite far away down the sequence, or the mutation could affect multiple genes.”

Gene expression studies have been largely carried out on blood because it is relatively easy to access. But blood is a complex mixture of cell types, such as T cells, B cells, and macrophages. This mixture means cell expression data can only be taken as an average.

“When cells are all mixed together, it’s really difficult to understand the function of a gene product at a tissue level – the genes that are expressed in a T cell are going to be completely different to those expressed in a macrophage, so you lose resolution.”

The same challenge occurs when studying endometriosis.

Separating out the mixture

“We want to know what is going on in the endometrial tissue but that is also a mix of epithelial, stromal, immune and other cells,” Dr McKinnon says.

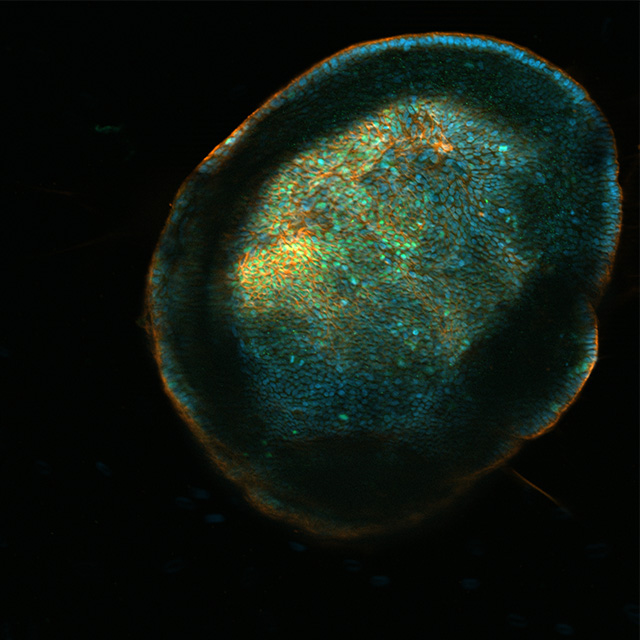

To overcome this challenge, he grows each cell type individually in the lab, which allows Dr McKinnon to conduct cell-specific expression studies.

“We’ve been able to grow the different cell types separately in the lab, and we’re also putting them back together to mimic what’s going on in the body – we’re creating three-dimensional replications of the endometrial tissue in a dish.

“We have the genetic data, so we can look at someone with a high genetic risk or a particular mutation, grow up their cells and see the effects directly.

“We are building up a repository of patients’ cells that we can manipulate to harbour different genetic variants to start to understand how a person’s genetics influence gene expression and the way disease develops.”

A personal approach

The next leap will be using cells from patients and the accompanying genetic data to screen drugs, or, in the future, growing up cells from lesions from a patient with endometriosis and testing which drugs specifically work for them.

Endometriosis is a very variable disease and having this personalised approach will make a huge difference to sufferers of a disease that currently has no targeted treatment.

“A patient can have different lesions in their body that respond to different drugs, so if we are able to target drugs to those lesions, which currently are being surgically removed, the impact will be significant.”